Ang Lee’s critically acclaimed Brokeback Mountain, set throughout the 1960s, tells the story of two men who fall in love while herding sheep through the American West. Widely described at the time as a “gay cowboy movie”, (a “cruel simplification” according to Roger Ebert), it was praised for its depiction of homosexuality, and the performances of its two leads. While defining it as merely a “gay cowboy movie” is reductive at best, the film does indeed take many aspects of the Western genre and cowboy iconography, and subvert and recontextualise them under a homoerotic lens. This was not the first film to do so, as several films in the 1960s used similar methods of subversion to depict homosexuality, and implied homosexual love between two men. I would like to explore these films, in particular Andy Warhol’s Lonesome Cowboys and John Schlesinger’s Midnight Cowboy, and and view them in relation to society perceptions of both homosexuality and the western film genre.

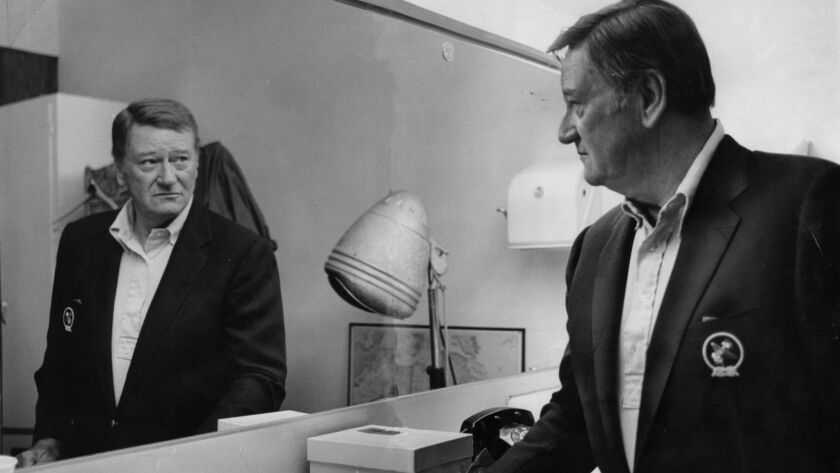

In a now infamously controversial interview with Playboy magazine in 1971, John Wayne, after reaffirming his commitment to white supremacy and doubling down on his belief that Native Americans were being selfish in wanting to keep their land, stated that Americans were fed up with Hollywood producing perverted films. When pushed to specify the films he was referring to, he replied with Dennis Hopper’s Easy Rider, as well Schlesinger’s Midnight Cowboy. Expanding on this, he said –

“Wouldn’t you say the wonderful love of those two men in ‘Midnight Cowboy,’ a story about two fags, qualifies?”

And, just to ensure he wasn’t misconstrued by using a positive adjective in relation to being gay, he elaborated –

“As far as a man and a woman is concerned, I’m awfully happy there’s a thing called sex. It’s an extra something God gave us. I see no reason why it shouldn’t be in pictures.”

Two years before that interview, America saw the release of John Wayne’s True Grit, still widely considered to be a classic of the western genre. In fact, Wayne won an Oscar that year for his performance as Marshal Rooster Cogburn, in the same year that both Jon Voight and Dustin Hoffman were nominated for Midnight Cowboy. As the face of the western genre at the time, and still one of its most famous and defining actors, it’s uncomfortable to hear Wayne express these views. It is, however, representative of the prevailing opinion and mindset of not only the western genre, but of American-midwestern culture in the 1960s. Indeed, western films were often used as a means of highlighting these conservative ideals and political views, with writer Simon Brandl stating, “the Western served as means of symbolizing its inherent values in political process… Wayne embod[ied] conservative values inherent to the genre in his movies”. It becomes evident, so, as to why Schlesinger, himself a gay man, chose to direct Midnight Cowboy – a film that, while there is plenty to criticise in relation to the sexuality of the lead characters, made incredible use of cowboy and western iconography and symbolism in order to explore, at its core, the love between two men. However, just before the release of Midnight Cowboy, there was Lonesome Cowboys, a film created by Andy Warhol and Paul Morrisey.

Initially working with Schlesinger on Midnight Cowboy, Warhol grew resentful when he believed Schlesinger to be poaching his scene, and thus set out to create his own cowboy themed film – even naming it Lonesome Cowboys as a direct parallel to Schlesinger’s film. Far more explicit than Midnight Cowboy, (the film’s previous titles included Fuck and The Glory of the Fuck), Warhol’s film opens with a seven-minute long, borderline pornographic display of heterosexual sex. Only growing more bizarre from there, the film follows a group of cowboys who stay at a ranch. The cowboys spend much of the film almost naked, and are often seen fighting and wrestling shirtless. What’s interesting, perhaps, about these sequences is the air of intimacy that seems to surround the fights and their aftermath. Following one of the fights, one of the cowboys lovingly caresses the mouth of another, and it’s clear there is a deep bond between the men. These fight sequences also serve to satirise the overt seriousness of masculinity in Westerns –

“The camp aesthetic of Lonesome Cowboys took further aim at the self-importance that had infused Westerns since the 1930s. Mocking the warrior-masculinity of traditional cowboy mythology, Warhol included an extended campground scene where the mostly naked cowboys share sleeping bags and cavort in an extended homoerotic wrestling match.” (Le Coney & Trodd, 166-67)

The casting of Joe Dallesandro as the lead is important, too, to the film’s homosexual coding. An out bisexual, Dallesandro was discovered the year previous by Warhol and Morrisey, and was cast in their film Four Stars. On Dallesandro, critic Vincent Canby wrote “His physique is so magnificently shaped that men as well as women become disconnected at the sight of him.” Indeed, Dallesandro continued to be an influence and iconic presence in gay subcultures, and featured prominently on the album covers for bands such as The Rolling Stones and The Smiths. A verse in Lou Reed’s “Walk on the Wild Side” references Dallesandro’s his role in Warhol and Morrisey’s film, Flesh, another film made in direct opposition to Schlesinger’s Midnight Cowboy.

The amateur nature of the film hindered it, however, as the film’s production was loose and unfocused, and it resulted in a film with a messy narrative, and characters without any defining qualities or characteristics. Writing on the film for The New York Times, Vincent Canby viewed the content of the film as not “so much homosexual as adolescent. Although there is lots of nudity, profanity, swish dialogue, and bodily contact, it has all the air of horsing around at a summer camp for arrested innocents.” It’s hard to disagree with his description of the piece, but the symbolism and ideals behind it were extraordinary for the time. By taking these typical masculine and straight-coded characters and placing them in an explicitly homosexual environment, Warhol and Morrisey create a truly unique and important piece of LGBT cinema.

Schlesinger’s Midnight Cowboy was released in the summer of 1969, and while undoubtedly critically acclaimed, was controversial for its homosexual themes and subtext even before its release. Initially set to receive an “R” rating, the film instead was rated “X” following a consultation with psychologist Dr. Aaron Stern, who “feared the adverse effect of the “homosexual frame of reference” on youngsters”. The film itself centres on Joe Buck, who comes across at first as quite a stereotypical Western cowboy-type. He travels to New York to work as a hustler, where he meets ‘Ratso’, a homeless con man. The pair grow close, and as the film progresses, Buck’s past traumas are revealed. It is a film intimately concerned with the relationship not only between these two men, but also Joe with his own sexuality.

Joe and Rizzo form a bond, and soon end up living with each other in squalor. Joe is determined to make it as a hustler, a job placing him in direct opposition with the homosexual subtext of the film. Indeed, Joe is terrified of his own sexuality, undoubtedly linked to his past trauma hinted at throughout the film. When he does engage in homosexual acts, it is by necessity. Rizzo, too, is terrified of his potential homosexuality and his love for Joe Buck, constantly using homophobic slurs, referring to Joe Buck’s cowboy apparel as “faggot stuff.” Joe even makes reference to John Wayne following this exchange – “John Wayne! You wanna tell me he’s a fag?” Rizzo is overtly aware of the shifting ideology and coding of western culture, while Joe represents the past – the standard John Wayne American cowboy.

Rizzo’s death serves as the ultimate symbol of society’s views on homosexuality at the time, through his death, heterosexuality dominates. Rizzo’s death is mirrored decades later in Brokeback Mountain in the death of Gyllenhaal’s Jack Twist –

“it is the more effeminate, more diminutive, more expressive, and ultimately less complacent protagonist whose pound of flesh is demanded. When Ratso Rizzo dies a bleak, unheralded death of an unspecified, incurable, and invisible disease while riding on a bus in search of a new and better future with Joe Buck, Schlesinger succeeds in eliminating the threat of queer contamination.” (Osterweil, 38)

Joe no longer has to make a so-called choice between his relationship with Rizzo, and his pursual of women, life takes that choice away from him.

In the decades that followed, the image of the cowboy would continue to be used as a means of representing homosexual in a more palatable way for middle America. The Village People rose to prominence in the late 1970s, with Randy Jones portraying a cowboy as a member of the hand. In an interview with SFGN, he stated “I don’t want to say it was genius, but part of the well-crafted plan was that we appealed to these various audiences and they felt like we were representing them”. He went on to discuss his presence in media and magazines at the time – “Those magazines were intended for little girls, but I’m telling you, the little gay boys read them, too”. I feel like these quotes epitomise the necessity of using the cowboy image as a display of homosexuality. Furthermore, even more recently than Brokeback Mountain, Anna Kerrigan’s recent film Cowboys tells the story of a man and his transgender son as they flee through the Montana wilderness. Again, the film uses cowboy-based symbolism and visuals to explore deep LGBT themes, building upon the foundation set in the 1960s through films such as Midnight Cowboy and Lonesome Cowboys.

Works Cited:

- Arnold, JW. “Cowboy Reminisces About Village People Career”. SFGN, https://southfloridagaynews.com/Music/cowboy-reminisces-about-village-people-career.html, 19 Jul 2017.

- Balio, Tino. “United Artists : the company that changed the film industry”. University of Wisnconsin Press, pp. 286 – 291, 1987. Accessed through archive.org – https://archive.org/details/unitedartistscom00bali/page/290/mode/2up.

- Bommersbach, Jana. “Homos on the Range – How Gay was the West?”. True West, https://truewestmagazine.com/old-west-homosexuality-homos-on-the-range/, 01 Nov 2005.

- Brandl, Simon. “The Depiction of Homosexuality in US-American Movies and Its Reception in Society”. University of Marburg, 2012. Accessed through grin.com – https://www.grin.com/document/337201.

- Comenas, Gary. “Andy Warhol’s Lonesome Cowboys (1968).” warholstars.org, https://warholstars.org/lonesome_cowboys.html, 2006.

- Ebert, Roger. “Love on a Lonesome Trail – Brokeback Mountain Review.” RogerEbert.com, https://www.rogerebert.com/reviews/brokeback-mountain-2005, 15 Dec 2005.

- Floyd, Kevin. “Closing the (Heterosexual) Frontier: “Midnight Cowboy” as National Allegory.” Science & Society, Spring, 2001, Vol. 65, pp. 99-130. Accessed through JSTOR – https://www.jstor.org/stable/40403886.

- King, Jack. “The gay ecstasy of the Village People”. BBC, https://www.bbc.com/culture/article/20200804-the-gay-ecstasy-of-the-village-people, 05 Aug 2020.

- Le Coney, Christopher & Trodd, Zoe. “Reagan’s Rainbow Rodeos: Queer Challenges to the Cowboy Dreams of Eighties America.” University of Toronto Press, Canadian Review of American Studies, Vol. 2, 2009, pp. 163-183. Accessed through Project Muse – https://doi.org/10.1353/crv.0.0035.

- Nelson, Rett “Critics call for John Wayne Airport to be renamed after interview resurfaces”. East Idaho News, https://www.eastidahonews.com/2019/03/critics-call-for-john-wayne-airport-to-be-renamed-after-interview-resurfaces/, 02 Mar 2019.

- Osterweil, Ara. “Ang Lee’s Lonesome Cowboys.” FilmQuarterly; Spring 2007. Accessed through ProQuest.